💳 Visa & Plaid: The DOJ Applying Learning from Tech

How the DOJ action with the Visa & Plaid acquisition is a learning from technology antitrust.

In January of this year Visa announced a $5.3 billion acquisition of Plaid. This month it was announced that the DOJ filed an antitrust lawsuit to block that merger, stating that Visa is a monopoly in the online debit space with Mastercard having only 25% of the market to Visa’s 70%.

We talk a lot about antitrust here, and I like to write about it given its salience to the current technology market conditions, so I was happy to see an antitrust case that’s both tech and economics, or in this case, finance related. The reason being that it’s hard to fully compare antitrust cases being brought against Google and other big tech companies to others, even to that of Microsoft… but this one is similar. Similar enough that the DOJ is learning from past mistakes.

Why Plaid?

Plaid, for those of you who aren’t familiar, is a company who helps fintech products like Venmo, American Express, and even your bank, connect to other banks, linking your accounts for easy transfers, balance lookups, categorization of purchases, and more. When you log into Venmo and add your Chase Checking account, you’re using Plaid behind the scenes. They are the middleman, providing a seamless API for connecting banking institutions in a way that banks themselves are unable, and rather, unwilling to do based on competition. These APIs provide a standardized experience for fintech companies, like Venmo, so that they do not need to deal with the fragmented state of technology amongst all of the banking and finance industry.

Imagine having that data and ability to move money as a competitive advantage to make your own banking products. Plaid’s product puts it at the middle of all of the banking industry, and is able to track consumer saving, spending, and investment habits from over 11,000 banking institutions around the world. This is what makes it so valuable, and so scary, to companies like Visa who want to maintain control of their monopoly on the market, a monopoly they have come by via deep-seeded banking contracts.

The case

From the lawsuit:

Visa seeks to buy Plaid – as its CEO said – as an “insurance policy” to neutralize a “threat to our important US debit business.” Visa is a monopolist in online debit transactions, extracting billions of dollars in fees annually from merchants and consumers. Plaid, a financial technology firm with access to important financial data from over 11,000 U.S. banks, is a threat to this monopoly: it has been developing an innovative new solution that would be a substitute for Visa’s online debit services. By acquiring Plaid, Visa would eliminate a nascent competitive threat that would likely result in substantial savings and more innovative online debit services for merchants and consumers. For the reasons discussed below, the proposed acquisition violates Section 2 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 2, and Section 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. § 18, and must be stopped.

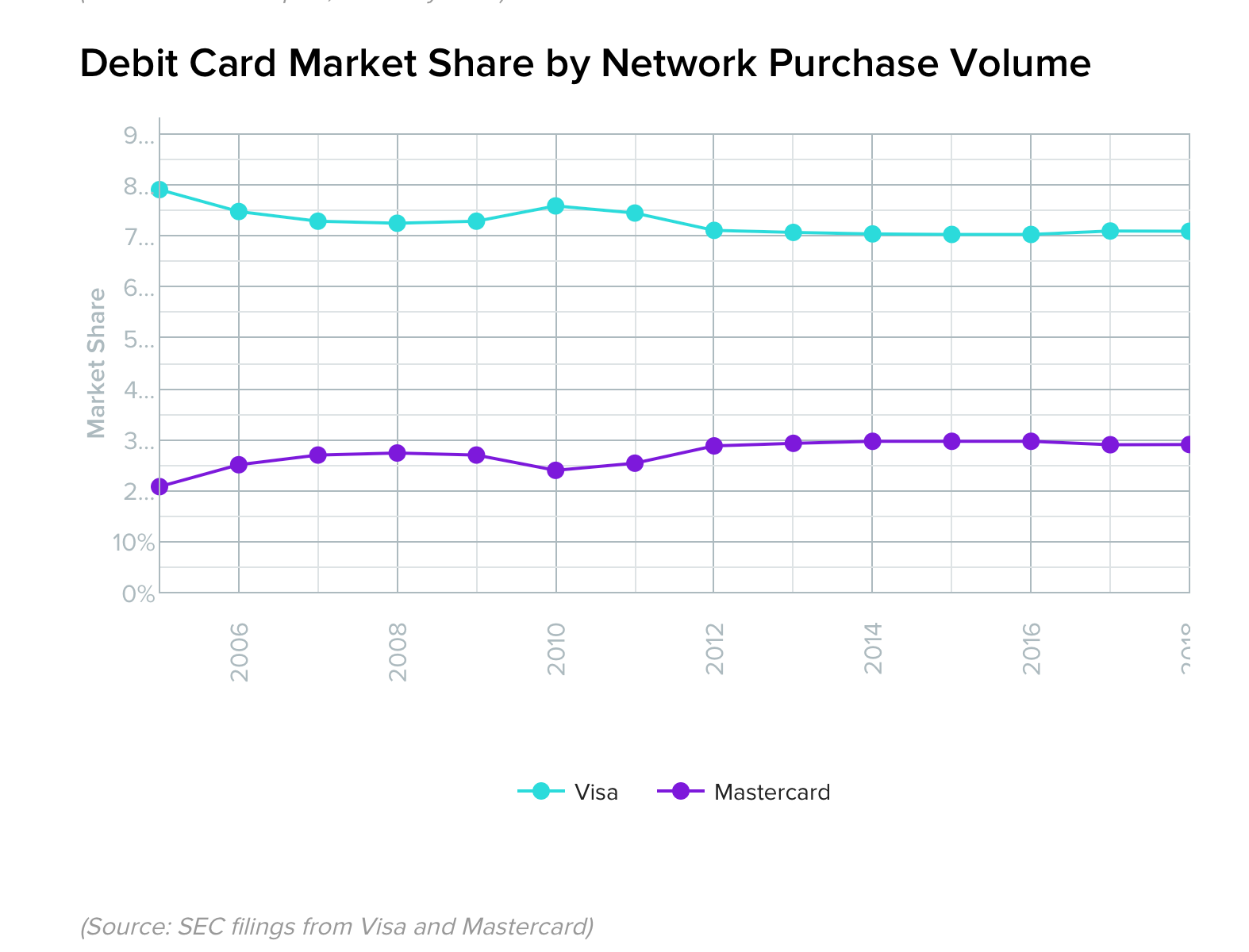

This single paragraph that sits on page one of the DOJ antitrust case against this acquisition says it all extremely succinctly: they believe that Visa has a monopoly on the online debit market and they want to eliminate a threat. They go on to back this up with a claim that Mastercard, their only serious rival, has not gained market share beyond the 25% they’ve been holding on for years, and that Visa edges out it’s competition with long-running contracts.

Mastercard, Visa’s only longstanding rival in online debit services, has a much smaller market share of around 25%. For years, Mastercard has neither gained significant share from Visa nor restrained Visa’s monopoly. Mastercard’s participation in the online debit market has not translated into lower prices for consumers, and this appears unlikely to change. For example, Visa has long-term contracts with many of the nation’s largest banks that restrict these banks’ ability to issue Mastercard debit cards. Visa also has hamstrung smaller rivals by either erecting technical barriers, or entering into restrictive agreements that prevent rivals from growing their share in online debit, or both.

Doing a bit of Googling, we can even see they aren’t wrong when it comes to purchase volume.

But that’s only the tip of the iceberg, as the real DOJ case looks specifically at this acquisition as an anti-competitive practice in and of itself, and the long-term contracts with banks as the tying that helps it edge out competitors. A clear no-no when it comes to the Sherman Antitrust Act which sees this anti-competitive behavior as a reduction of consumer choice. That reduction of consumer choice usually leads to inefficient product pricing, and therefore, is bad for the consumer.

Things in common

At first glance, one could argue that the Google case and other big tech reports are very different from the Visa/Plaid case. Tech giants leverage the internet, unlimited scale, and 0 marginal costs for new customers. It’s that which makes them so valuable, but also vulnerable to competition. If someone wants to create the best search engine and compete with Google, they can. When they do, anyone can type their address into a search bar and hit enter.

However, when we look at the DOJ case against Google, the main argument is the tying of Google Search as the default on mobile devices and how they pay (a lot) for those slots to edge out competitors. These defaults are not changed often, and it’s been said that 50% of all Google searches come from Apple devices. This anti-competitive behavior they are pressing on with Google is synonymous with the long-term restrictive contracts with banks put into place by Visa.

There are also similarities in the discussions around Facebook and their previous acquisitions in the social space, namely Instagram and WhatsApp. While right now there is no formal antitrust lawsuit, the DOJ widely agrees in their latest reports that Facebook has engaged in anticompetitive behavior to neutralize a threat with those acquisitions. It’s that type of mistake that the DOJ is trying to prevent.

From the DOJ:

These entry barriers, coupled with Visa’s long-term, restrictive contracts with banks, are nearly insurmountable, meaning Visa rarely faces any significant threats to its online debit monopoly. Plaid is such a threat.

Learning from the past

There’s a lot more great reading in the case itself, but the long-and-short is that the DOJ sees this acquisition as the loss of a disruptor to Visa’s stronghold on the debit market, and they don’t want to let an organic competitor grown out of computational banking industry trends become usurped by Visa.

This is a learning by the DOJ after looking at the previous big tech companies, their acquisitions, and the result of the market dominance they now question. In the case of Google, Facebook, Amazon, and less so, Apple, these companies acquire startups in a space that I believe is harder to conceptualize and easier to view in hindsight rather than try and predict future growth of said startup in the market, like Instagram and WhatsApp discussed above.

The DOJ wants to get ahead of the same errors they made in the past through blocking mergers that are easily identifiable as anti-competitive, and for those that aren’t, look back in hindsight for tell-tale signs. Fortunately for them, Visa/Plaid may be just the example they are looking to set for a case that’s a bit more cut and dry, and also one that is arguably more important than Google or the big tech players.

From Ben Thompson in one of his weekday updates:

That is the thing about friction, and non-zero transaction costs: their presence limits scalability, but deepens moats. This has a counterintuitive implication: I find deals like Visa-Plaid to be even more pressing than Google’s deals to prop up Search. All of the same factors that make Google big also make it trivial to use something else, which gives Google incentives to make sure their product continues to generate significant consumer benefit. Meanwhile, the difficulty in building up a payment network of Visa’s scale means it is that much more important that the company not be allowed to buy out competitors.

I agree with the statements here. Google, even as it does have contracts to set itself as the default search engine, those settings are changeable. It’s still anticompetitive tying, but when you are looking to avoid the next antitrust lawsuit, preventing a mistake of an allowed acquisition based on very clear reasoning from the leaders at Visa themselves, it’s a good time to act before it gets too messy. If they don’t they will need to unbundle later on, and as we have seen with tech, that can be extremely hard to do.